The forgotten and ignored are my tribe.

I’ve heard it many times over the past couple of years that one must “find their tribe.” Conceptually, I understood this, but I only recently resonated with it.

As soon as I realized that the forgotten and ignored were my tribe, I had an undeniable need to find them, love them, and be of service to my tribe.

Who are the forgotten and ignored?

- When I was 8, they were the elderly living in a nursing home… so I spent time with them regularly, every week, for over four years.

- When I was 14, they were the still-active seniors who didn’t have anywhere to go… so I played pool with the sharks, cards with whomever was interested, and taught some to make a few new crafts.

- When I was 18, they were struggling families who just needed a home… so we built a few with Habitat.

- When I was 29, they were border babies and medically fragile children who couldn’t live at home, but didn’t need to be in a hospital full-time… so I held them, played with them, fed them, cared for them, and put them to bed every week for a year.

- When I was 32, they were the teenagers who were left behind when their church grew big enough to split up… so I spent every week that year talking with and listening to these young people, and thoroughly enjoying the tumultuous, wonderful lives they were learning to live.

- Now, they are the homeless and the working poor. People I’ve been peripherally involved with caring for over the years, but am now laser focused on being of service to.

Who are these “homeless” people?

The most prevalent images we have of homeless in the US are made up of people who are lazy, mentally ill, criminals, drug addicts, or chronically homeless.

Something like this, right?

What if I told you that:

- Only about 15% of the homeless out there are chronically homeless individuals, and only some of those fit the above description?

- That about 1/3 of our homeless are families?

- Or that 1 in 10 are veterans.

- And almost 1 in 10 are unaccompanied children, fending for themselves?

- Or that about half of our homeless are just people who could no longer afford housing where their jobs were?

- And that around 35% of our homeless go without any kind of shelter on any given night.

- Or that over 80% of our homeless are temporarily homeless and just need a little help?

These people — yes, people — aren’t who we’ve been told they are. Many are skilled, passionate, kind, and just need a little help to get back on their feet.

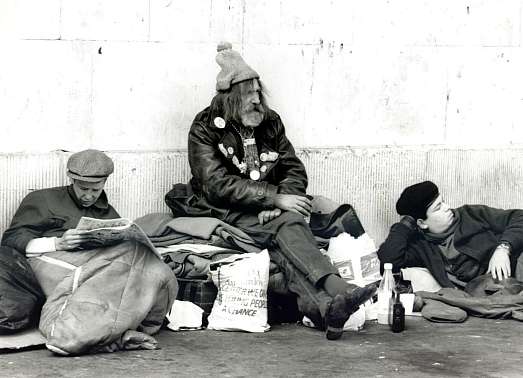

I’d like to introduce you to a few.

Walter — A master-recycler, he diligently collects and turns in recyclable materials in order to buy food and an occasional bed. Also: has the kindest, gentlest demeanor on the block.

Tyrone — A former chef and current caretaker of a dying friend. Skilled with food, he can make a masterpiece of the scraps we throw out.

Smitty — a former plumber and current water-feature, using his skills as a plumber and his circumstances as a wheelchair-bound amputee to entertain the masses.

Matt — An independent contractor with a good living: the house + the wife; lost everything after an injury. Still takes odd jobs to get by. Says that people think he rescued a stray cat, but in reality, she rescued him.

Curtis — Not sure where Curtis came from, but he wants to be a motivational speaker and volunteers around the shelter, just making sure everyone is taken care of.

Carey — Had a good office job until it disappeared. Lived in this minivan with her 2 kids after that, unable to get an interview as long as she didn’t have an address.

Calvin — A friendly soul who greets and warmly welcomes everyone. A window-washer by trade, hasn’t found much work since being injured.

Not really who you pictured when I mentioned “homeless,” right?

Just the facts.

The homeless population in the US is around 600,000 people, and this exceeds the number of beds by more than 200,000 each year. Another issue: the beds aren’t always located where they’re needed, so beds can still go empty.

Here’s the thing, though: beds in emergency shelters are more expensive to offer and maintain than permanent (or even semi-permanent) subsidized housing, per person, annually. Surprised?? I was.

That doesn’t even include the enormous cost disparity between medical expenses when treating those with and without permanent shelter — it costs half as much to treat the same injuries and illnesses when the person has permanent shelter and their hospital stays are much shorter (~4 days shorter, which is a savings of over $2k each time).

Add to this that we have laws on the books designed to target homeless and have them serve jail time for simply not having anywhere else to go (including regulations against loitering, begging, or even sleeping in one’s own car). These costs run anywhere from $14k to $20k per person, annually, whether it’s just overnight stays or a year’s sentence.

Here’s the funny thing about housing and employment: you can’t get a job if you don’t have an address, but you can’t get an address if you don’t have a job. Where’s the middle ground?

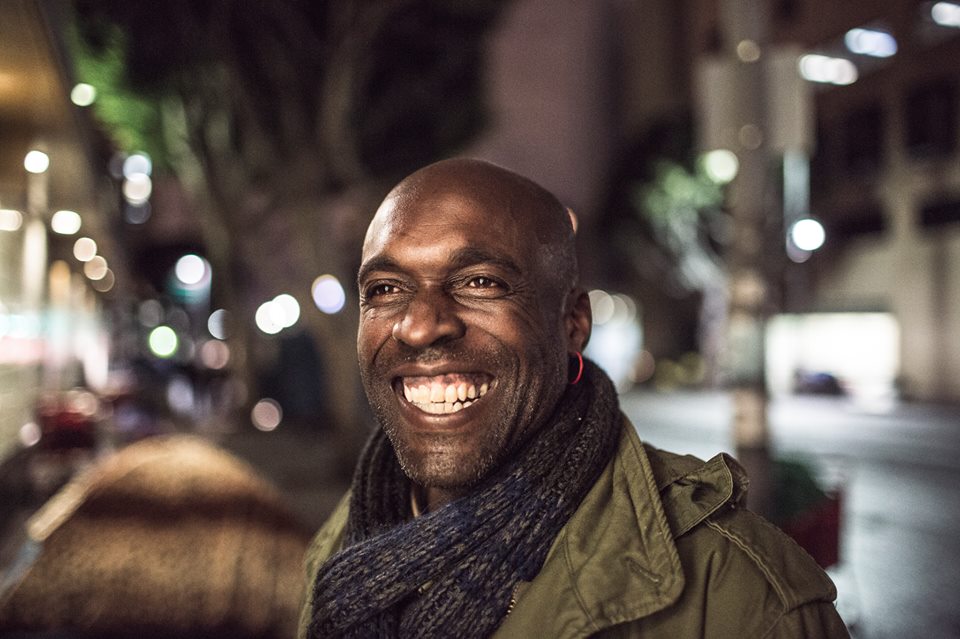

Some middle ground: TINY HOUSES

Concept Rendering by Techdwell for Portland, OR.

With a per-unit cost of about $12k, how would tiny houses be used to address these issues?

- For the temporarily homeless (or, ideally, those who are not yet homeless), this would be the temporary living situation that keeps one from living on the street or in their car (with their kids) and still provides a stable address so employment can be acquired, maintained, and allow a family to save enough money for their own place once again.

- For the chronically homeless, this is a space that provides consistent shelter, a modicum of stability, and a small community who all take care of each other — reducing illnesses, cost of treatments, and jail time/expenses just by introducing some shelter stability.

Some folks ask — and understandably so — how can we afford to build tiny houses for our homeless? I’d offer, “how can we afford not to?”

Also, in 5 cities around the US, we’ve already got tiny house communities planned. Allow me to introduce you to the new homeless community: a city block full of functional, safe, sustainable housing.

Concept Rendering by Techdwell for Portland, OR.

Not what you normally picture as “homeless shelter,” is it?

Why them? Why now?

I’m fortunate to have a support network amazing enough to prevent me from joining the ranks of “homeless.” There is no doubt in my mind that without my family, I would have been. How many of us have this kind of support, though? In the US, most families live hours away from their extended families and 1/3 of Americans are only 1 paycheck away from homelessness.

One. Paycheck.

Think about that.

If you’re a single-parent household and your kid gets sick, you are the only person able to care for them (daycare and school will send them home if they’re sick). How many days of work can you miss and still make your rent? Still afford food, insurance, utilities?

Let’s say you’re a college grad working your way through a competitive industry, and you end up in a situation where there are more competitors than positions? How many paychecks could you go without before you couldn’t support yourself any longer?

How much money do you have in savings right now? How long would that last you?

If I ever end up in a situation where I need a shelter like this, I’d like to know that they exist.

One third of this country is teeter-tottering on the edge of being in this situation. We cannot afford to continue ignoring it — hoping it gets taken care of.

Conventional solutions have definitely helped in emergency situations, but if we ever want to return to a prosperous nation full of citizens who are contributing in every little way they can, we need to rethink how we go about caring for our citizens.

Would you be proud to call Matt or Tyrone your neighbor?

I would.

And I intend to.

Join me and let’s do some amazing things together.

XOXO,

**Images courtesy of John Hwang